This article also appears in:

Introduction

A question that comes up regularly is regarding clef usage with the bass clarinet. The majority of bass clarinet music is written so that the notes the clarinet player sees correspond to the same fingerings they would use on any other clarinet. Meaning, it is written in treble clef but sounds an octave lower than B♭ soprano clarinet (a major ninth lower than concert pitch).

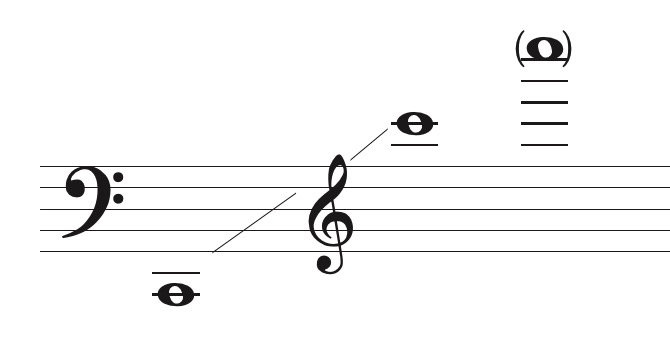

Bass clarinet music does, however, also get written in bass clef, particularly in older orchestral music. The logic is that some composers want to notate in the octave in which the instrument sounds. Due to the huge range of the bass clarinet, however, one clef is not enough. In the transposed sounding octave, a low-C bass clarinet spans from two ledger lines below the bass clef staff up to at least the C two ledger lines above the treble clef staff (and my own fingering chart goes an octave above that!) So rather than using up to eight or eleven ledger lines above the bass clef or an ottava (8va)marking, composers will switch to treble clef for the upper range. This means that the treble clef should be played an octave higher than where it is read, but that is not always the case, and this is where the confusion begins.

There are four notational practices used when composing for bass clarinet ‑ French, German, Russian (Mixed), and Italian. Here is an explanation of each practice and the different ways composers may use the treble and bass clefs when writing for the bass clarinet.

French Notation

- Uses Treble Clef in transposition of a major ninth.

French notation writes everything in treble clef, utilizing a transposition of a major ninth from concert pitch. The clarinetist uses the same fingerings for the bass clarinet note as they would on a soprano clarinet, but it sounds an octave lower. The logic is that the clarinetist does not need to think about different fingerings but plays everything as they normally would. This results in more ledger lines, as the low C is written in the space below the fourth ledger line beneath the staff, but this is only one more ledger line than the clarinetist is accustomed to reading. French is the most common way of notating for the bass clarinet and creates the least amount of confusion.

It should be noted that this does not mean that French composers do not use bass clef at all. For example, Dukas writes in bass clef in The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. When they do use bass clef it is often in the German notation, as described below.

German Notation

- Uses Treble and Bass Clefs, both in transposition of a major second.

German notation uses bass clef in transposition of a major second from concert pitch, like clarinet, rather than a major ninth. The logic is that the treble clef then continues this same transposition. This means, however, that the clarinetist must play the treble clef notes an octave higher than they normally would when reading the printed note. The majority of bass clarinet music that uses bass clef is in German notation.

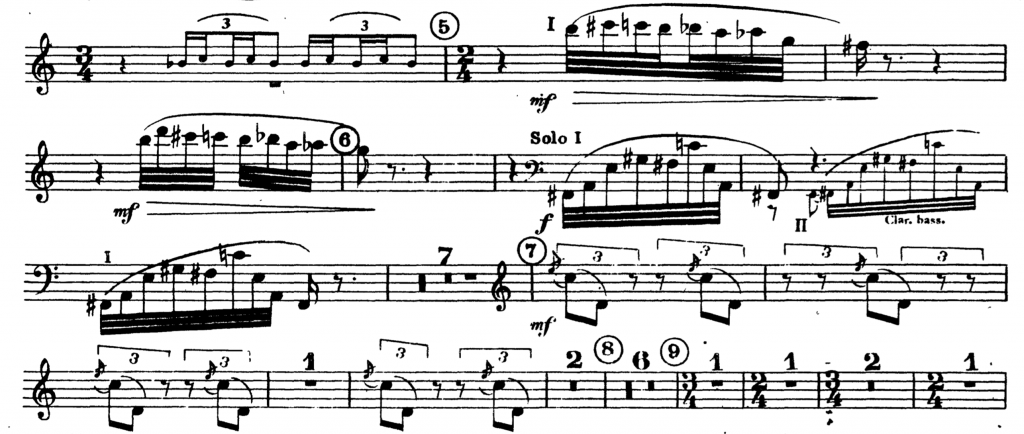

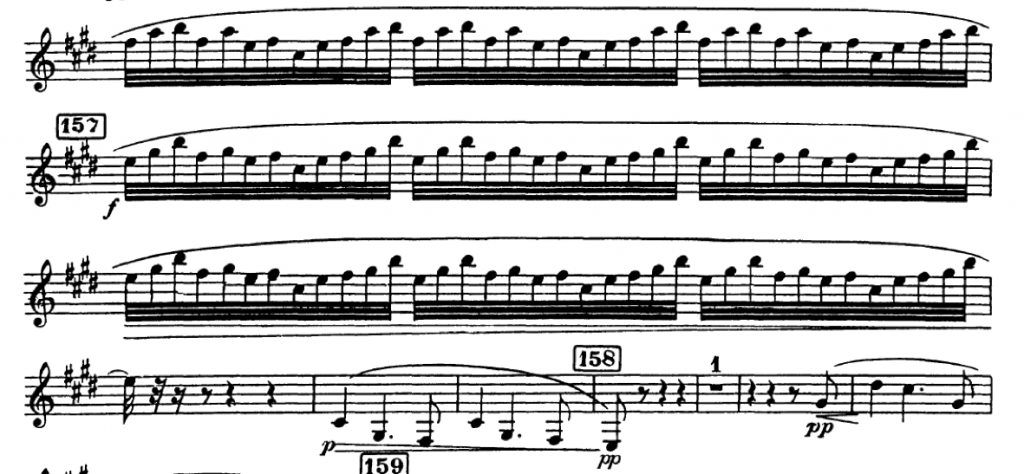

As you can see in Figure 5, from Salome’s Dance, Strauss uses the bass clef for the lower register. In the second bar of rehearsal mark J, however, there is a change to treble clef. This line is clearly meant to continue upwards through the clarion register rather than jump from the clarion F down to a throat G♯ at the clef change. Rather than using four ledger lines above the bass clef staff he switched to treble clef, and this is meant to be played an octave higher than a clarinetist usually would when reading those notes.

Again, it should be noted that not all German composers use this notation. Mahler, for example, used French notation.

Russian (Mixed) Notation

- Uses Treble and Bass Clefs. Bass clef is in transposition of a major second, Treble clef is in transposition of a major ninth.

Perhaps keeping the transposition of a major second does not make sense, but rather it is more logical to use bass clef for the lower register and when the clarinetist encounters treble clef they should read it as the normally would. This is how it is done in Russian (also called Mixed) notation. The bass clef is read as a transposition of a major second like German notation, but the treble clef is transposed by a major ninth like French notation.

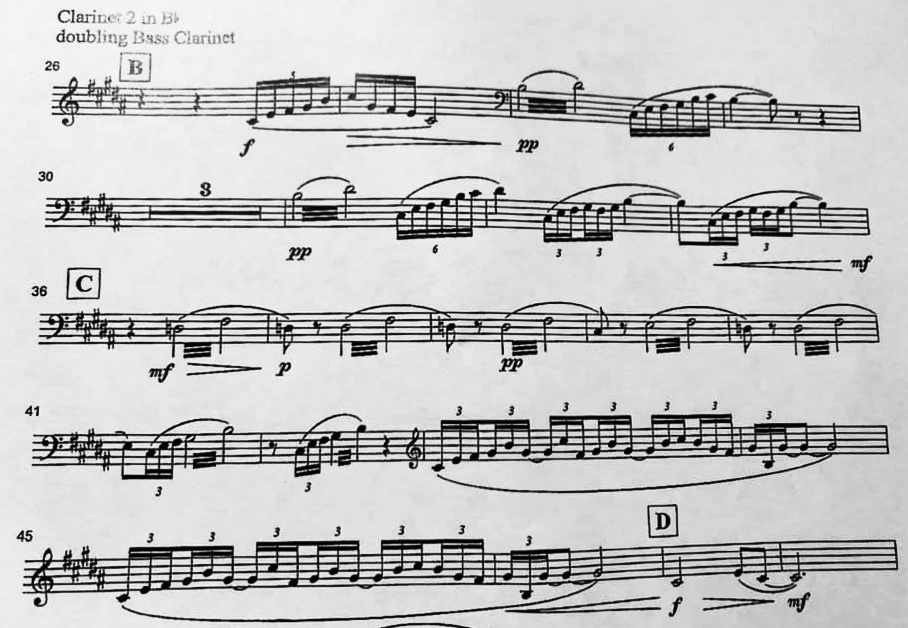

Figure 7 demonstrates Stravinsky’s use of this notation in the Rite of Spring. The line at rehearsal mark 2 is a descending B♭-A-G♯ in the chalumeau register, but he switches from treble to bass clef in the middle to avoid extra ledger lines.

Figure 8 is from the Bass Clarinet I part. While it is theoretically possible to play this treble clef passage an octave higher, it would be very awkward technically for the fingers and no composer would have written that high for the bass clarinet in 1910 when Stravinsky composed this. This should be played with the fingerings a clarinetist would normally use, therefore using a transposition of a major ninth.

Italian Notation

- Uses Treble and Bass Clefs, both in transposition of a major ninth.

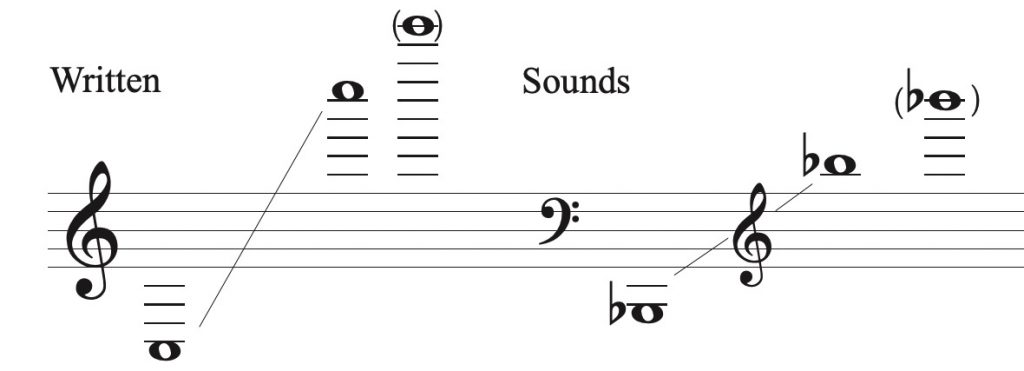

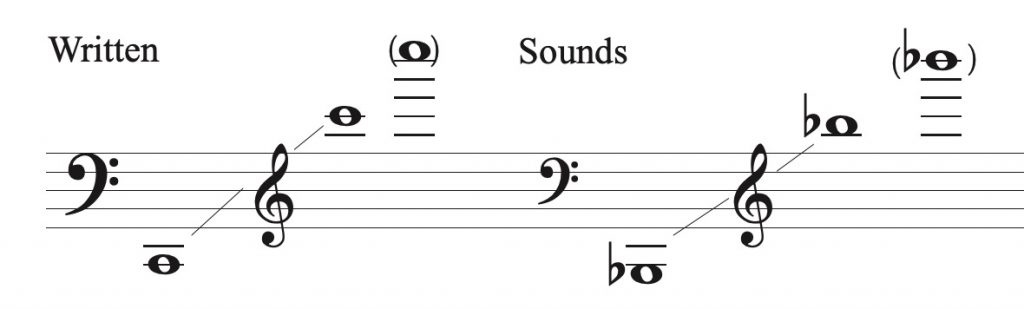

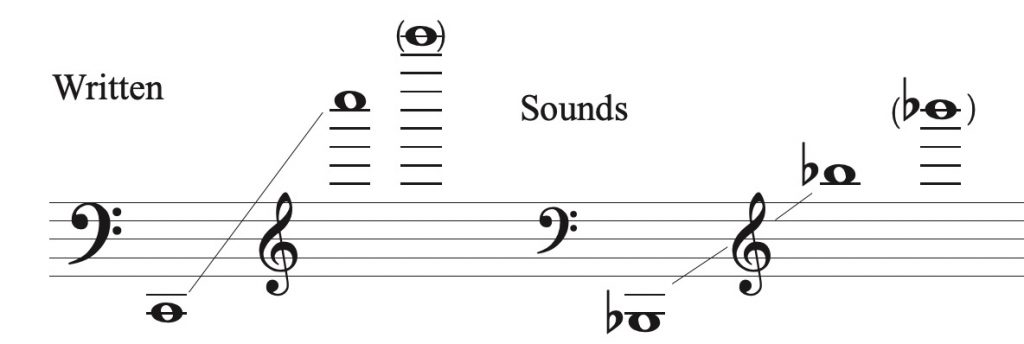

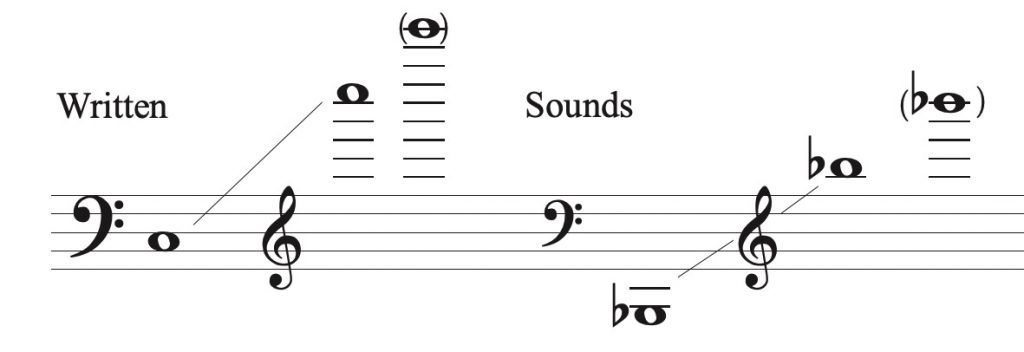

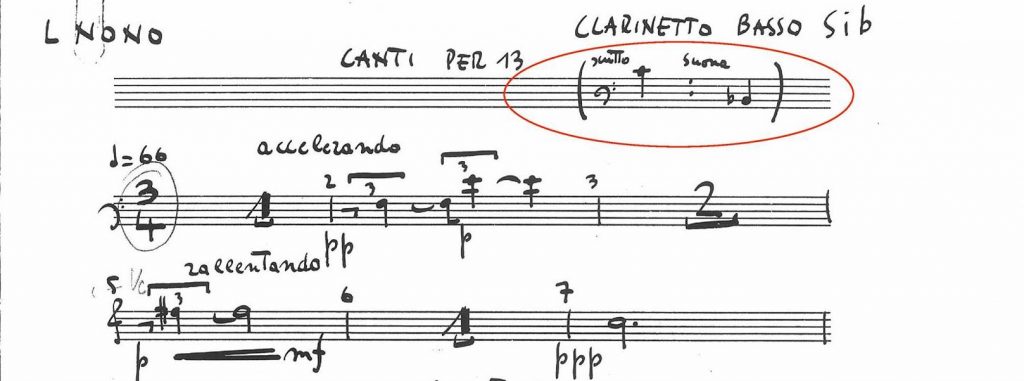

There is a fourth way of notating the bass clarinet, although I have personally only ever encountered it once, in Canti per 13 by Luigi Nono. Harry Sparnaay states that he had seen it with some regularity from some Italian composers in the past, however not in a long time.[1] I am therefore calling it Italian Notation to follow with the naming convention. Nono states at the top of the bass clarinet part that the bass clef is in a transposition of a major ninth – scritto (written) C4 above bass clef staff : suone (sounds) B♭2 in the staff – therefore needing to play it an octave lower than if reading as German notation. The first note in Figure 10 is a low F, not thumb F. The treble clef also transposes a major ninth, therefore read as a clarinetist normally would.

[1] Harry Sparnaay, The Bass Clarinet: a Personal History, trans. Annelie de Man and Paul Roe, 3rd ed. (Barcelona: Periferia Sheet Music, 2017), 48-49.

Bass Clarinet in A

A composer using bass clef notation will follow the same principles if writing for bass clarinet in A, transposed accordingly. Thus, German notation in A stays at a transposition of a minor third throughout, and Russian notation is a minor third in the bass clef and a minor tenth in treble clef.

Which notation is being used?

Unfortunately, it is not always clear which notation a composer is using. These national conventions can be a starting point, but as previously stated they are not a rule, and there are composers from many more countries than just these four. Often applying some logical thinking to the context of the music will help answer the question.

One of the reasons to change clefs is to avoid ledger lines. There may be some notes that overlap across both clefs, as a composer normally would not change clefs for single notes that cross the threshold when the rest of the material stays in the other clef. If the part has been in bass clef but changes to treble clef, check if it made sense to change clefs to avoid ledger lines. If so, it should probably be played up an octave.

Look at the lines and the direction of the music. If a clef change creates a large leap in what would otherwise be continuing a more linear line, play it in the octave that continues the line, like in the Strauss excerpt in Figure 5 or the Stravinsky excerpt in Figure 7.

Look at the material in each clef, and whether it makes sense for it to be in one octave or the other. Figure 11 is from the Australian composer Maria Grenfell’s River Mountain Sea. She uses both treble and bass clefs, but to play the treble clef as written would put it all in the same range as the bass clef material. There would be no point in using two clefs in this case. She is using German notation, and the treble clef is to be played up an octave. The clef change in bar 43 is another clue. The line continues from the B at the top of the bass clef to the adjacent C♯, but now written in the treble clef.

Consider the range as well. Composing for the bass clarinet in the altissimo register is a relatively new development, especially in an orchestral setting. If playing the treble clef up an octave results in many very high notes, it is probably supposed to be down an octave.

Look at the full score. A concert pitch score will be written in the sounding pitch and octave and can immediately answer the question, or it may become evident based on the musical material in the other instruments.

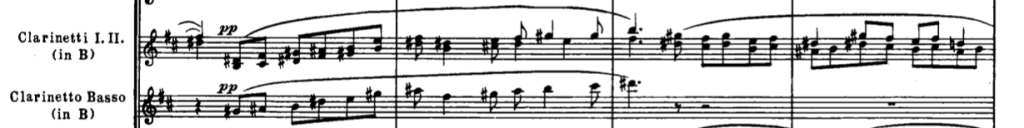

Figure 12 is from the beginning of Rachmaninoff’s third symphony. This score is transposed and notated the same way as the parts are, so it is not helpful by providing the sounding pitches. However, the bass clarinet part can be compared to the clarinets and bassoons to determine that the Russian notation is being used. If the treble clef section in the bass clarinet part were played up an octave, it would be in closer harmony with the clarinets, and unison at the end of the bar. While this is possible, it is not the most effective scoring. Rachmaninoff could have written for three B♭ clarinets instead. Playing it with a ninth transposition puts the bass clarinet in a better octave for the scoring, and the following bar is in a closer harmony with the bassoons, which would be more logical.

Figure 13 shows a treble clef excerpt from later in the piece where the bass clarinet, if played an octave higher, would sound higher than the clarinets, in addition to being very high in the altissimo. The context makes the intention clear.

If it is not possible to see the score before the first rehearsal, listening to a recording and trying to hear the part within it can be beneficial.